Interview with Fracture

Fracture on UK jungle history and pirate radio, the parallels with punk culture, and the freedom to build bridges between scenes without pigeonholing artists.

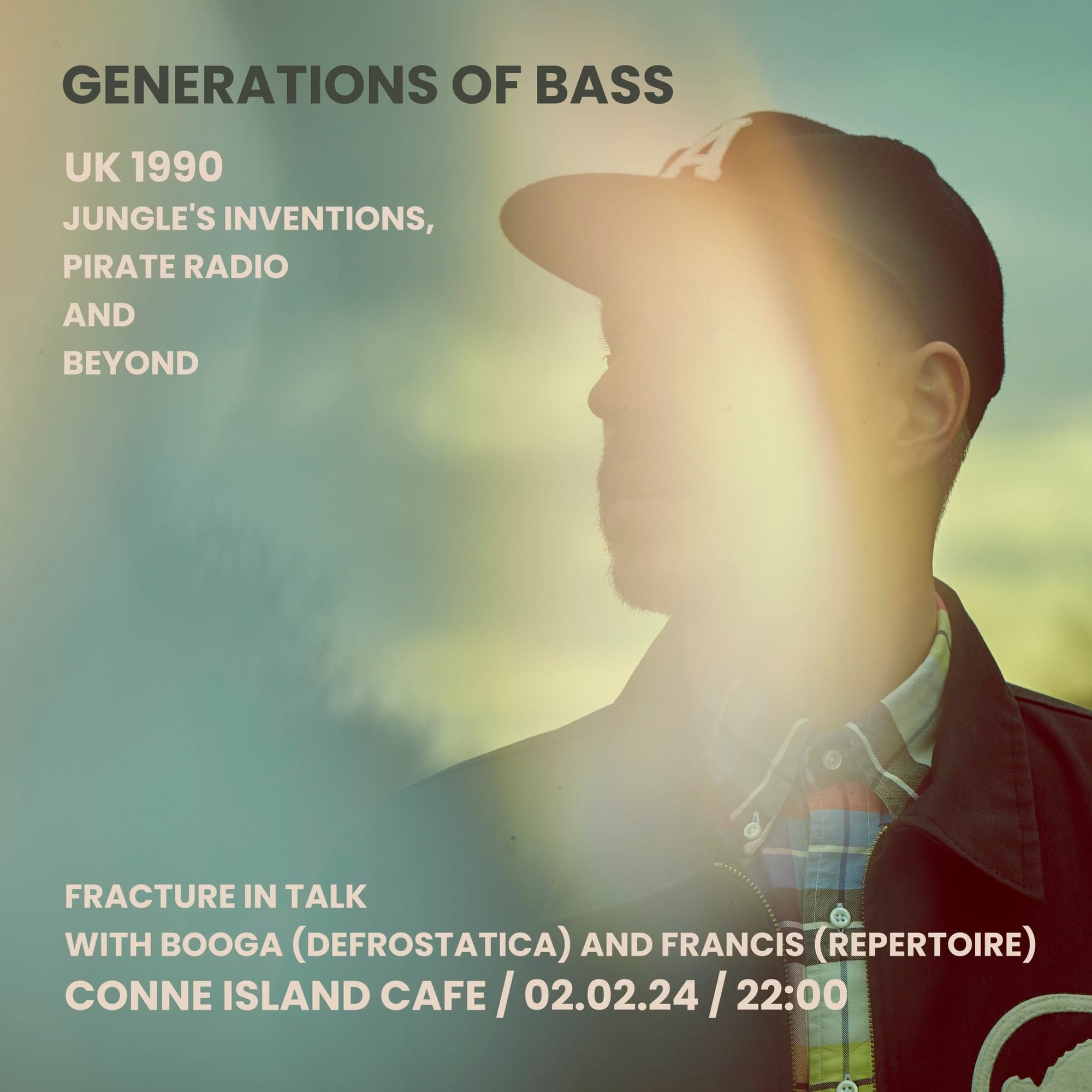

Just before he took to the stage at the Conne Island venue in Leipzig, Germany in February 2024, Fracture kindly took the time to answer questions from Francis, the audience and myself. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Francis: We are here at Conne Island Cafe today and welcome a special guest: Fracture from London, UK. We're going to dig into the history of UK jungle music and pirate radio because Fracture did a great research project on that topic recently. I'll hand over to Booga, who is looking back into history as we are diving into the year 2012.

Booga: The last time you played at Conne Island was in 2012. Overall, it was a time of exciting musical development with both post dubstep and footwork jungle emerging in DJ sets. Ben UFO played here at Conne Island, Martyn played here, Machinedrum played here, and Fracture. Within a few months a lot of different musical developments were brought to an ecstatic audience. With this context, what was your point of view when these different genres and ideas from different places collided and created something new?

Fracture: 2012 was indeed an interesting time and I think to set it up, I will go back a few years previous to that and mention dBridge and Instra:mental and the Autonomic series that they did. They did a series of podcasts and a series of music releases that took the framework of drum and bass music, blew it apart and looked at it from a much more spacious point of view which came from dubstep, I suppose. And then in 2012 it opened the doors for a lot of other influences to be able to be brought into drum and bass. The Autonomic stuff took drum and bass and presented it in a half tempo form, which opened the doors for a kind of hip hop to be mixed in. And what that did, at least for me, as a DJ and a producer, it made me start to look for music from outside the drum and bass world, which I wasn't doing at that tempo at the time.

So then that was a lot of music from the States, I remember mixing in music by people like Machinedrum and Mr. Carmack, you know the L.A. beats in general. And so that whole thing was quite exciting because up until then, drum and bass has been very, very drum and bass. Which was great, but the Autonomic thing opened the doors for the music and the influences to reach further but also to take on new influences. And I think 2012 was definitely a year where that started to happen. And then along with that was the kind of mix with footwork from Chicago, the Teklife stuff that made sense all of a sudden with drum and bass.

Fracture in 2012 about his label Astrophonica, the relation of Footwork and Juke to Drum and Bass and a DJ’s approach to mix up slow/fast tunes. Filmed by LXC, edited by Tina Gleichmann.

Booga: When the UK label Planet Mu released the first edition of the Bangs & Works series in 2010, many producers realised that there is oldskool jungle at 160 bpm with the same tempo range. So you, Om Unit, Sam Binga took it from there and came up with footwork and juke influenced tracks that had that uptempo energy. Is that how you came up with the track Get Busy?

Fracture: I want to just pause and shout out Om Unit because I think he was the guy that helped me find new influences for my music. He comes from a hip hop and scratch DJ background. So he was starting to bring in hip hop and a lot of U.S. influences. And then Get Busy was just my take on a mix of where I'd come from, so jungle and drum and bass with this kind of new stuff that I was hearing primarily from Chicago, the footwork stuff. Yeah, Rashad and Spin and Teklife.

Booga: You released Get Busy under your alias Dawn Day Night on Exit Records in 2012. The label was founded by dBridge, who was part of the drum and bass producer group Bad Company. He kind of emancipated himself from the stadium sound to a leftfield drum and bass that eventually led to a half-tempo subgenre called Autonomic with a podcast series of the same name. When he released your footwork/juke influenced 12" vinyl, did you feel it was an active decision to support the hybrid development of footwork and jungle influences at that time?

Fracture: Yeah, definitely. I think dBridge has always been really good at giving artists space to try new stuff on his label Exit Records. So it felt just comfortable artistically working on that label, working with dBridge. He definitely opened those doors and helped me join those dots.

Francis: We've been now in 2012. But this is already ten years back and now we're going to travel like another twenty years back – to 1993, that's a bit frightening actually. I'm going to play a few beats of a song you know and we’d like you to comment on that.

Fracture: So yeah, that's Helicopter Tune by Deep Blue from 1993 and that's a classic jungle sound, but also very clean and very stripped back. So I would say that was one of the tunes that probably paved the way for drum and bass. Because it's got everything that jungle had, but it was also a bit more linear in the arrangement. Less crazy, less all over the place and a bit cleaner and based around one groove. Whereas a lot of the jungle stuff before that was based on various different grooves throughout the whole track.

Francis: Could you describe a bit more what was going on music wise at that time and just to zoom in on, why this track brought up something new at that time?

Fracture: I guess the interesting thing about this one is that previous to this a lot of the big jungle tracks at the time all had vocals in them. And this was one of the first tracks that wasn't focused around the vocal. You had Burial by Leviticus, I think that was maybe a year after this, but around that period you had a lot of tracks with vocals in them.

But this one was really stripped back, so it presented the music in a new way. Previous to that – in 1991, 1992 – there was a lot of UK hardcore stuff, which was a bit more ravey, lots of stabs and lots of big ravey hooks and riffs. Whereas this one was not necessarily built around any particular sort of riff or hook or anything like that, it was much more built around a drum and bass group.

Francis: One of the reasons we wanted to talk with you was your series of interviews and mixes called 0860 where you discussed the emergence of jungle and drum and bass with a focus on pirate radio. So, why this specific focus? How did you decide you wanted to do something about pirate radio?

Fracture: Well, that's how I found the music. I grew up in London, and when I was about 12 or 13, in 1991 or 1992 the whole scene was a subculture. It wasn’t like it is now, where it's a much broader and available culture. So the music was hard to find, the culture was hard to find. And one of the ways in which you found it was via pirate radio. So I found it by just being in my bedroom, listening to, going through radio stations and hearing the music. And, it gave me an insight and a taste for this world that I didn't really know existed but all of a sudden I had a window into.

And I think a lot of people found the music the same way as well. Obviously it was a big influence for me, so the 0860 project was very much a personal project for me. I wanted to show people where I had come from as an artist and what my influences were. But I also wanted to highlight how important pirate radio was in bringing this underground and subculture music to where it is today. Because at that time no national radio stations were playing the music. It was impossible to find on national radio. It wasn't really spoken about in the media or the press, not like it is today. And obviously there was no internet. So it took for illegal pirate radio stations to present that music.

I wouldn't be here as an artist if it wasn't for pirate radio stations. So I thought it was important to show that. Also I think that it's probably the same story for a lot of artists.

Booga: When we zoom out what pirate radio is, it actually is an illegal counterculture and it also is probably your first contact with DIY culture, right? Do you remember a time when someone told you stuff about why this is illegal? Did you have a clue about what's going on, what these guys risked at that time? And was it just the music that you were hooked on or also the fact that it was different or dangerous?

Fracture: I'm not sure if the danger necessarily played a part, but I was definitely fascinated from a cultural point of view as well as by the music. I was so young that I didn't necessarily understand, but I was aware that culturally it felt different from what I was seeing on the TV or reading or hearing on national radio. I'm a big music fan anyway, right? So I was going from listening to Michael Jackson or whatever on national radio and then I would flick it over and listen to some hardcore on the pirate radio station. And it immediately felt different. It felt completely different. And I suppose as a youngster, it feels like you found it yourself because it's not presented to you in the wider channels.

Fracture, Booga, Francis at Conne Island Café 2024 / Photos by Tina Gleichmann

Booga: To add some context and perspective from the first generation of DJs in Leipzig: We were recently talking about the emergence of the local drum bass scene and how radio played an important role for us, but with commercial radio stations, because we didn't have any kind of illegal pirate stations here. In the late 80’s we were fascinated by the sample-cut-up style music that was popular at the time, like Doctor in the House by Cold Cut or House Arrest by Crush or Pump Up the Volume by Mars or what Bomb The Bass was doing. These tunes definitely played a role in our developing interest in breakbeat music as such. So when hardcore breakbeat music from acts like Shut Up And Dance, Rebel MC, The Prodigy spilled over into the record shops over here, we felt it was connected to what we'd heard before and went from there. And I would also say that music television played a big part at the time. So the excitement of breakbeat music and jungle drum and bass came to us through the mainstream media. We missed out on the illegal pirate radio culture that helped develop the genre in the UK at the time. We're coming at it from different angles, but we're still here. Do you see the similarity in the excitement around breakbeats?

Fracture: Well, I think that sampling and breakbeats fit into the story because it's diverse in a way. It is in itself inherently illegal. It's stealing other people's music, right? And reinventing it. So that fits into the story somehow as well. And particularly the jungle stuff was quite often made by people who didn't necessarily have a background in music and just wanted to make music, but didn't have any knowledge of how to do that.

And all of a sudden the samplers and so on gave people the ability to steal other people's music and put it together. So yeah, I think there is definitely something exciting. I still find sampling breakbeats incredibly exciting. And perhaps that is because it is somewhat anti-establishment.

It's not just that, though. I'm excited by taking something that exists and presenting it in a new way. And in fact, some of my favourite records, for instance, the Helicopter Tune that you played, was made by people that don't have a background in music. And I find that sometimes culturally more exciting than music created by people that have years and years of training.

Francis: So pirate radio is not just about the radio bit, but also about recording tapes which during your research you have put online on SoundCloud.

So now we can listen to – and some are really crappy – recordings from the 1990’s. Could you describe a little bit of the tape culture at that time? There's a personal story to that. I lived at that time in a smaller city called Dessau. There have been British exchange students and they played recordings from Kool FM on tape – and that's how I learned about drum and bass. In a very unlikely situation, basically, at that time, I was surrounded by punk music and ska. But it's interesting because it's also a two step sound in a way. So, I would be interested in both of these aspects. The two step aspect, but also then the tape aspect.

Fracture: I'll just touch on the punk thing first, because I think that electronic music and jungle in particular have a lot of parallels with punk music. For a lot of the things that I was just talking about: The fact that punk music is quite simple. Not necessarily made by extremely talented instrumentalists and I put myself into that same bracket as well. I don’t play any instruments. I played the guitar a bit, but it's more of an expression. And I think that's why punk and jungle and rave music share a lot of similarities. It's not necessarily about being a virtuoso instrumentally. It’s much more about giving yourself a voice, giving a culture, a community a voice.

I made tapes every weekend: I would record pirate radio every weekend onto a cassette and then take them into school on Monday and share them and you swap them with other tapes for your friends. Bearing in mind I was too young at this point to go out to any raves. This was still when I was like 13, 14, 15 years old. So that was my only way of hearing this music. And the tapes became your archive. I always remember one particular time a friend of mine recorded Origin Unknown's remix of Dead Dread onto a cassette.

And we, we just sat there and we ran it like ten million times, constantly, for the whole night. So tape culture became a way of archiving the music pre internet. Also it links again with the piracy thing, because you're recording music that's being played on an illegal radio station and then you're making essentially an illegal copy of it as well.

Francis: It was maybe also an opportunity to cut out the advertisements that were part of the program.

Fracture: It’s funny actually, because those have now become my favourite bits of my old tapes.

Francis: Really? Okay (laughing).

Fracture: Well, because obviously I know all the tunes now so I can listen back to the tapes and still get excited by the music, but the adverts provide a real window into what was happening culturally at the time. Because you could hear about all the raves, all the parties and I suppose now they've become cultural artefacts in that not only do they document music, but they document things like how language has changed, how slang has changed, and even how accents have changed.

So, the London accent has changed drastically since those tapes have been recorded. What I found in this archiving process, I started off from a sort of musical point of view, and then realised that this is also providing an archive of accents, language, dialect, and culture as well. And so thus the adverts have become some of my most treasured bits, yeah.

Francis: I recommend readers go to the 0860 project website https://0860.fm and check it out. One of the things that really shook me was that there was music playing and …

Fracture: … then someone would really shout over it yeah. Well, you know, they would advertise the record shops, they would advertise the parties but they would also advertise restaurants as well on Pirate Radio. So you'd have jungle music and then you'd have the advert break and there'd be someone who maybe was a friend of the Pirate Radio station, their uncle had a restaurant or a bakery or cafe or something like that and there would be an advert for this cafe. It'd be like if you come in and say, “I heard about you on Kool FM”, and then you get a free something. There was an advert for a bagel shop actually on Kool FM, and MC Det did the advert for it. The place was called Mr. Bagels, great stuff.

Francis: It could be interesting to discuss this commercial aspect against today's understanding of how underground works. I personally despise any advertising but I find it a very interesting example of how community building works. When something happens within a community and it sort of organically blends …

Fracture: … in, right? Yeah, definitely. I mean pirate radio was about music of course but it was totally about community as well. And it was about giving communities a voice that didn't have a voice and maybe weren't able to advertise in any other way.

Francis: Okay, let's play a short recording from a DJ talking over the music..

Fracture: That's Nick Powell "You're through until 10pm tonight. With loads of new material. So don't go away. Don't even go to the toilet."

Francis: Don’t you even dare to leave for the toilet.

Fracture: You know it's true because – and I know, I keep saying it's not like today when we've got the internet – but the pirate radio station played it, and if you didn't tape it, that's it. It's gone. Never to be archived ever again. So he's right, you know, don't even go to the toilet because you might miss something that you'd never ever hear again.

Booga: Pirate radio stations were illegal, so I wondered how they managed to not get shut down by the authorities? Is pirate radio still a thing today? Did some of the stations even manage to get licences and become legal?

Fracture: Yeah, three excellent questions. So, if they were illegal, how did they avoid getting shut down? Well, most of the time they didn't avoid it. They would get shut down a lot.

The way in which it worked is you had a studio, and you had a transmitter from the studio that would transmit to a midpoint. And then from the midpoint, it would transmit to people's radios. So, it was quite easy for authorities to track you down and cut you off. But it was not as easy for the authorities to find the actual studio. Pirate radio stations would quite often get cut off. But, because they were incredibly resourceful, they would always find a way to come back on, quite often, that same weekend. The pirate radio stations would know the authorities personally by name and the authorities would know the pirate radio stations as well by name. Unless you were caught in the act of doing it, then the authorities couldn't prove anything and thus you couldn't be arrested. So you had this kind of little cat and mouse thing going on. It was a constant battle. There was a certain respect. The stations had respect for the authorities, in that the authorities were just doing their job. So if the stations conducted themselves as professionally as they could, the authorities would kind of not go after them as much, they'd go after the stations that were causing more hassle.

You asked if any stations went on to get licenses. Well yes, Rinse FM is probably the biggest, it started out as a pirate radio station. Their story is incredible, really. They were incredibly driven and professional about how they did it. They gained a community license for a short period of time, and then they've got a full license to legally broadcast on the FM. Kiss FM back in the 90s as well. Cool FM has recently been acquired by Rinse, so it's now also a legal station.

And then you also asked if there are any pirate radio stations today. And this is a really good question and an interesting one. In terms of the music that we are into and we do, there's a couple, but not loads. But there are a lot of in London at least, there are a lot of Turkish pirate radio stations. I think there's quite a lot of African pirate radio stations as well. So again serving the community, playing music and giving news and information that otherwise is not available. So yeah, pirate radio stations do definitely still exist, but in a different world.

Booga: Let's talk about your beginnings now. What made you go from listener to …

Fracture: … player? Well, my dad is a guitarist. My dad was always in bands. Still plays in bands now. So, there was always a kind of understanding of being a musician. You know, creating music. I grew up in East London, where a lot of the pirate radio stations were based. So I was fascinated on a deep, deep level and I just wanted to be a part of it. Through my dad being a musician, I knew that it would be possible for me to also get into making that music, much to his disappointment.

Booga: So your first thought was, "I want to make some beats and I want to be on that tower and represent that as a DJ"?

Fracture: You know I started off playing the guitar and I was into grunge music and punk music and stuff. But around about the same time the whole rave and jungle thing was starting. I never particularly got good enough at guitar to even be in a punk band (laughs). But I felt, I'm going to do this. At school, everyone was listening to pirate radio stations. Everyone. At the age of 14 years old. At school, there'd be the phone numbers for the pirate radio stations written on the desks, the frequency, the names of the DJs and stuff – it was absolutely everywhere.

Booga: There were still some hurdles to take, like buying Technics turntables.

Fracture: Oh, I didn't have Technics for a long time. I started on belt drive Soundlabs, horrible yeah. But, DJing was just something that I had to do. I know that sounds a bit corny, but it was so ubiquitous that I just wanted to be a part of it on an inside sort of level. Yeah, I wanted to go beyond just listening to it. Yeah.

Booga: So you bought the records, you had some shitty players. You were at home, you practiced and what was your first gig?

Fracture: House parties with loads of teenagers getting very drunk. That was quite a big scene as well. As I got older, like illegal squat parties and stuff like that and then the first actual gig. Was it any good? I don't know, I can't remember honestly.

Booga: When did you start making beats?

Fracture: I started quite early on the family PC that had an audio recorder. So you could record sections of audio into the computer and then I edit them up. I'd record hip hop tracks and just loop one bar, and loop it for ages. That was the early kind of fascination, just recording stuff on my mom's computer which had maybe like 30 seconds recording time before it would crash.

Booga: Would you say that it is important to be limited when trying to make music?

Fracture: Yes, very much so. Limitation is really important. Again, taking it back to the pirate radio thing, it was born completely out of limitation. The limits being, no one else is presenting this music, so we got to do it ourselves. We don't have anywhere to do it, so we're just gonna do it in a squat with a crappy DJ mixer. And I think limitations, yes, in art and music is important because I think it pushes you to really master what it is that you're trying to do, crafting the message that you're trying to convey.

Francis: When you produce music, what are your limitations today?

Fracture: That's a good question, because there are no limitations now. I would say it's entirely possible to make a hit record on your phone. Software like Ableton gives us not only vast options, but it also gives us the ability to never have to commit to an idea because you can constantly undo it, constantly save different versions. Which is great in one way, but the limitations I experienced working on my mum's computer, was that I couldn't save multiple versions, there was only one stage of undo. Once you did five or six processes, that's what you had. So it just kind of makes you think a little bit more about what you want to do, and what the results of you doing that are. It's a tough one because now we have all the options we need, right? Hard disk space is no longer a problem.

Booga: How would you encourage young artists you're working with, to hold on to a concept and not spacing out from one idea to another?

Fracture: I always try to work really quickly. Because I think that in itself is quite a limitation. That is one of the key things that I would always say to younger artists to try and work as quickly as they can. Because the longer you sort of dwell on things, the easier it is to lose track of what it is that you're trying to do. And I'm saying this from experience because I've done it so many times and got sort of four or five hours into something and realized that I've got caught up in minute details that don't matter at all.

Booga: What is more important to you as an artist? Reinventing a music genre from within or reinventing yourself as an artist?

Fracture: I've always liked playing with genres. I've always liked playing with what is possible and I've always liked challenging myself but also challenging the preconceptions of what a genre is. I think that kind of goes hand in hand. So that in one way progresses me and challenges me as an artist. But then the result of that is often challenging the genre itself and trying new things.

Booga: When we met before, you said you like to flip things, right? I wonder if that was inspired by Busta Rhymes, when he said he is “flipping things” to become the greatest. The first time I heard of you as a producer was when you were making drum funk. Jungle is of course the common thread through all of your excursions to halftime, juke, footwork, turbo and also electro. In 2022 you presented the 0860 pirate radio project with jungle at its heart. I feel like you're testing what is possible in all this. What is next?

Fracture: Well I'm always interested in what I call the bits in between. So, you can take that back to 1992, 93, which is when it was sort of hardcore. It was before jungle had become proper jungle. It was this very experimental sort of period in between. Another era I have in mind is the kind of early dubstep and grime period. When it didn't necessarily have a name yet, and it was the bits in between. I think it was the same with Autonomic and also true for footwork, as it was a little bit in between jungle and footwork. Just before COVID I was playing a lot of electro and mixing that with jungle and slower kind of breakbeat stuff, and that felt really interesting as well. There seem to be a few people doing that as well. There's Lucy from Berlin, she was doing cool stuff, kind of halfway electro, halfway jungle at 130-140 bpm. That was really interesting. Then COVID happened and it messed that whole thing up. So where are we now? I don't know, it's a good question. It feels now more so than ever before that a genre is not as much of a constraint as it was previously. I think people are just doing whatever they want at different tempos.

Booga: Even from a DJ point of view?

Fracture: Yeah, from a DJ point of view as well. Which is good in some ways, but …

Booga: I sense a downside?

Fracture: No, no, it's not a downside. I quite like having the rules of a genre, to then be able to play with them. If there are no rules and there are no agreed set of parameters, then it's hard to break them. If things lose context slightly, because anything goes, it's a problem because we become unable to say, "Yeah, but what about the bits in between?"

If there are no rules and there are no agreed set of parameters, then it's hard to break them.

Francis: I have another question regarding limitations. So from the music that I know of you as an artist, and also as a label boss, it's always like very fit for the floor, very danceable. Do you consider that as a limitation as well or a problem?

Fracture: That's another really good question. Yes, that is certainly a limitation because there are just certain things that won't work in a dancefloor situation. But do I find that a problem or not? No, not really. To take you back to pirate radio stations, they did give certain records a platform that weren't necessarily getting played in clubs or on dance floors at the time. You'd hear certain songs on pirate radio that would become quite big pirate radio songs that wouldn't necessarily be big club tracks for the reason that they just didn't quite work in that situation.

Francis: But it's not like you have a whole hard drive full of non club music made yourself.

Fracture: Not really. I think what's great about having a label as well is that I can and have released music that is not immediately aimed for the dancefloor. There's one called Custom Tone which actually I did with my dad playing guitar on it, and that was very much not a club track. So, you know, having the label gave me the platform to be able to do that.

Booga: I like to come back to the flip mode of 2013, when footwork met jungle music. In an interview with XLR8R, Rashad from Chicago and Om Unit from Bristol talked about how they feed off of each other musically across the pond. In our days, where music is globally available, I'd say it's important to encourage people to build bridges in a way and hold on to that. When Rashad died a year later, do you feel that there's a chance gone, that bridge between the states and Europe or UK in particular?

Fracture: Yeah, that was definitely a moment. There was definitely a bridge there, you're right. I think particularly these moments in between, by definition, they only last for quite a short period of time, before people go off and follow their own solo career for a bit. All that bridge ended when Rashad passed. People went off and built on their own thing, you know? People like Taso, they continued that and developed the sound further. And likewise so did Om Unit, took it and went off in his own direction as well. So those kinds of bridges and those in between parts, they last for quite a finite amount of time. But I think that's what is quite beautiful about them, I think.

I think particularly these moments in between, by definition, they only last for quite a short period of time.

Booga: Yes, that is something that needs more understanding. If a DJ or producer is a big part of a specific scene or genre – if the person is gone, or is changing their mode, it sometimes feels like a part is really missing from the piece, and of the whole scene. It's like when Photek released the Solaris album and he only managed to put one drum and bass track on it between the house tracks, there was kind of a confusion back then, not in a relaxed way, but people were like "he betrayed us".

Fracture: Yeah. I mean, people get quite protective over the music they like. And they then put their own sort of projections of what they think an artist should be doing. And what's important to always remember is that, that an artist should be doing what they feel is the right thing to do.